EE209AS

Blockchain for Secure IoT Firmware Updates

Ahmed Refai and Eugene Wu

Abstract

As the Internet of Things (IoT) industry continues to grow, security systems need to develop to ensure that manufacturers can easily and reliably issue security updates to their devices. This project investigates a blockchain-based security update system that allows IoT device manufacturers to manage firmware updates for their devices through the use of smart contracts. IoT clusters can autonomously query the blockchain, and download the newest version of their firmware binaries as soon as they become available. The same smart contracts also manage device identity, and can be easily extended to enforce fine-grained permissions for different types of devices and users.

Introduction

Over-the-air (OTA) updates for IoT devices allow manufacturers to quickly and conveniently update devices that are already deployed in homes, industry, power grids, and more. As the number of devices a given manufacturer is responsible for maintaining scales, it becomes more difficult to manage the version control and update process required for every device. To solve this, manufacturers must construct their own OTA update management systems or push updates through a trusted third party. This has already been done for large, established manufacturers like Apple or Sony. However, smaller, newer IoT manufacturers do not necessarily have this infrastructure in place [12]. Firmware updates that are held on centralized servers are vulnerable to denial-of-service attacks, and this can delay critical patches from being applied to vulnerable devices. Even in the absence of attacks, a large number of simultaneous, legitimate update requests can overwhelm a small manufacturer’s servers. Firmware update systems also need to provide a guarantee of the validity of a firmware update, blocking malicious updates and keeping legitimate ones. In general, an ideal firmware update system would satisfy the CIA triad of requirements: confidentiality, integrity, and availability [3],[8].

Blockchain technology has been popularized over the last several years as a potential solution to security problems [1]. The concept was pioneered by Bitcoin as a digital currency (cryptocurrency) system. The currency uses a distributed ledger that records transactions made by network participants. Miners in the network contribute computing power to solve complex algorithms to “mine” the next block in the chain. Miners are compensated with Bitcoin in exchange for their hashing power. The system rejects blocks with false transactions – when a block is mined, other participants in the network can easily confirm if the block is legitimate or not. A given participant in the network does not have to trust other parties in the network, but can still trust that the results of this mining process are legitimate. Furthermore, the contents of all but the most recent block can be considered immutable and forever available for the public to access. Transactions in the network can be traced back as far as the beginning of the blockchain itself. All of these features of the network result in a transparent, trustless, immutable, resilient system for tracking the exchange of digital currency.

From this starting point, the concept of cryptocurrency has evolved to include smart contracts that allow users to implement arbitrary logic through the blockchain. A smart contract is published by an owner and exists at an address (its public key) in the network. Users and the owner of the contract can then interact with the contract, calling the functions the owner of the contract defined. For example, a smart contract could implement a simplified voting system, where participants can submit their public addresses to the contract and the owner of the contract can delegate votes to these voters as she chooses. A participant who has been granted a vote can then call a function in the contract to submit their vote, and the contract will collect the results and announce a winner. The contract is transparent and deterministic - its behavior is defined at the time of its publication and its code is available for inspection on the blockchain.

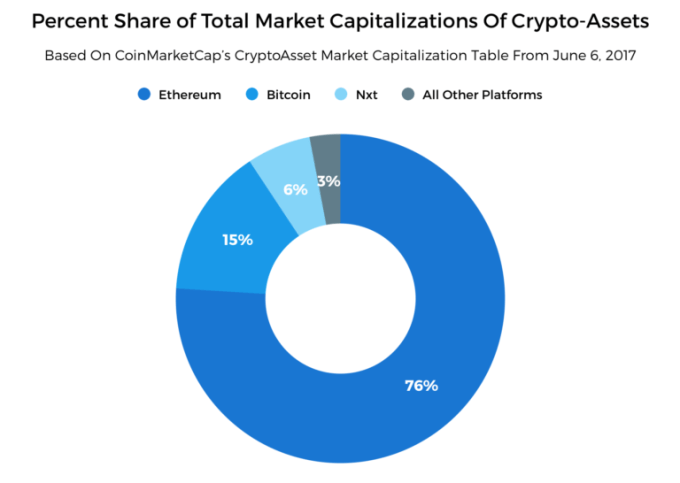

The cryptocurrency Ethereum began development in 2014 and became the first project to implement smart contracts. Since then, it has become one of the most popular platforms for developers to create their own dapps (distributed applications). The figure below shows that an estimated 76% of cryptocurrency projects are developed on the Ethereum platform and exchange coins on the Ethereum blockchain [13].

Different blockchains can vary in their rules and purposes; there are public blockchains adapted for the open exchange of value or information. There are also private blockchains ideal for use in enterprise. Private blockchains require new nodes to acquire permission to participate in the network. This allows manufacturers to whitelist trusted participants in the network and stay closed to the public. While Ethereum does have a public blockchain, Ethereum itself can be more broadly defined as a protocol. For this reason, it is a flexible tool for creating both public and private blockchains. There are several test blockchains that slightly differ from the main blockchain in their properties.

This project aims to implement a blockchain-based identity management and firmware update system for smart home sensors. The private nature of our blockchain as well as its immutability prevent denial-of-service attacks and ensure that updates pushed to the blockchain will be continually available to all devices [9]. The decentralized nature of this software distribution method alleviates stress on the manufacturers’ servers, instead distributing the burden of version control and update management to a trustless, distributed network. Furthermore, smart contracts are transparent, tamper-proof, and flexible, allowing for more device autonomy with regard to enforcing permissions. Finally, the blockchain provides a public ledger for manufacturers to easily audit successful and unsuccessful updates to their devices.

Attacker Model

For this project we assume a resourceful adversary that has access to many devices and miner nodes. The adversary is able to see data received through the blockchain on miner nodes, and is able to influence operations on end devices.

Network

We assume an adversary is able to observe network traffic and determine the contents of packets as they leave and enter a given network. This means that the adversary is able to determine the unencrypted contents of a given update file, and can isolate the manufacturer’s digital signature that accompanies each update. This information is not useful to an attacker as the private key cannot be inferred from such information. We also assume that the adversary is able to isolate a given device from its miner device. This only damages the given cluster and is not considered stealthy since the miner node will notice.

Blockchain

We assume the adversary does not control the majority of nodes on the blockchain network (miner nodes). This is a reasonable assumption as the adversary must be able to compromise each miner device individually, and there is no way for the adversary to propagate an attack through the actual blockchain network. This assumption allows us to guarantee that all transactions sent to the blockchain are legitimate and not forged. Currently, only the manufacturer is able to influence data uploaded to the blockchain.

Manufacturer

We assume that the manufacturer is not compromised. Our current implementation relies on a trustworthy manufacturer. It is therefore assumed that all updates pushed by the manufacturer are valid, and should be installed by the appropriate devices. This unfortunately gives rise to attacks on the manufacturer node that could lead to severe damages to the overall network and connected devices. The system does not protect against buggy or malicious firmware pushed by the manufacturer. However, given that the manufacturer node is appropriately secured, the system does protect against its impersonation. An adversary cannot push an update pretending to be the manufacturer as they would need the manufacturer’s private keys (one to sign the software, and one to sign the transaction).

System Overview

The system will consist of a private, permissioned blockchain that is managed by a manufacturer. The manufacturer maintains one or more nodes in the blockchain, and publishes a smart contract into the blockchain to control identity management, firmware updates, and any other logic that must be implemented for the system. Only the manufacturer has permission to add or remove miner nodes to and from the smart contract’s record. The smart contract is flexible and can be programmed to enforce permissions on its users. Smart homes are grouped into clusters of IoT devices that are connected to one or more “miner” nodes. These nodes act as gateways to the blockchain, interacting with the manufacturer’s smart contract.

Private Blockchain

A private blockchain permission system is preferable to an open one for this application, as it affords the manufacturer more control over their own ecosystem of devices. Participants (which will be the gateway nodes) must be whitelisted as “peers” by the manufacturer. A private blockchain is on an entirely separate chain from the frequently used public Ethereum blockchain (the mainnet). To start a new blockchain, one must create a genesis block. The genesis block sets the parameters that are also true for consecutive blocks. The data in every following block will depend on the preceding block in the blockchain, except for the genesis block. After creating the genesis block, nodes in the network can “mine” ether and receive and send transactions.

Smart Contracts

Ethereum provides a special functionality called a smart contract [14]. The Ethereum virtual machine (EVM) acts as a decentralized computer, executing contract functionality on a network of nodes. The smart contracts are coded in a turing-complete language called Solidity. Once published, they exist at an address in the Ethereum network, transparently, autonomously, and deterministically carrying out whatever logic with which they were programmed. In this system, we use smart contracts to provide an interface for manufacturers to publish new firmware updates and for gateway nodes to fetch those updates. Our contract allows the manufacturer to add and remove gateway nodes, and maintains a mapping of public keys to their corresponding nodes. Below, we include an excerpt of the Solidity code in our contract.

bytes public firmware; // Newest Manufacturer Firmware Binary

address public owner; // Address of contract owner

struct Node { // Instantiation of IOT sensor

string name; // Device Name

}

mapping(address => Node) public nodes; // Map addresses to devices

function pushUpdate(bytes new_firmware) public {

require(msg.sender == owner);

firmware = new_firmware;

}

This contract stores a dynamic byte array containing the most up to date firmware, the address of its owner (the manufacturer’s blockchain node from which the contract was issued), and a mapping between known addresses of miner nodes and the actual node structs themselves. We also see the pushUpdate function, which accepts the firmware binary as input and updates the firmware stored in the contract accordingly. Notice that the function requires its caller to be the manufacturer.

Smart Home Network

Because of the resource limitations and power constraints on most IoT devices, they typically cannot be instantiated as nodes in the blockchain network. The devices in each home instead interact with the blockchain through one or two gateways, which are full nodes on the blockchain. The setup for this network is well-accepted as a solution to integrating IoT systems with blockchain [2],[3],[6]. The gateway nodes interact with the blockchain on behalf of the devices, and relay any relevant results back to the devices.

Software and Hardware Tools

We used a Raspberry Pi Zero W running the Raspbian OS as an IoT device existing in a smart home. We implemented miner nodes on one Windows and one Linux machine. We used Geth, the Go implementation of Ethereum, as our main tool to construct and interact with our private blockchain. Geth utilizes the Web3 JavaScript API to assist in interacting with the blockchain. For contract testing, we used the Remix IDE to compile our code and Metamask, a browser extension that allows interaction with the distributed web, to publish and interact with contracts. We also use Python and Node.js to write the scripts to control interaction between different components of the system.

Firmware Update Process

The firmware update process consists of four steps:

- Manufacturer signs firmware binary file with private key, pushes to blockchain through smart contract

- Miner regularly queries contract to receive most recent version of firmware

- Miner regularly checks firmware version of sensors and actuators

- When the miner notices a discrepancy, it initiates an update of the device firmware

When the manufacturer wants to issue a new firmware update, they first sign it with their private key and then use the smart contract to add the signed binary file to the blockchain. The smart contract will only allow firmware updates originating from the manufacturer’s network address. Meanwhile, the miner queries the contract at regular intervals to update its copy of the latest firmware binary. The miner checks if the obtained copy of the firmware was signed by the manufacturer to ensure its validity. The miner periodically checks the firmware binaries of the sensors and actuators, and the miner compares their binaries to the most recent ones. When there is a discrepancy between firmware versions, the miner initiates an update of the corresponding device’s firmware.

Benefits of Solution

Our solution provides many benefits to manufacturers. First, it simplifies the firmware version control and distribution process. The manufacturer simply pushes an update onto the blockchain through the smart contract and it becomes immediately available to all gateway nodes on the network. Copies of the firmware will propagate throughout the network with no involvement from the manufacturer (i.e. the manufacturer is not required to distribute their software and incur the costs of serving multiple clients). This protects the manufacturers from potential denial of service attacks and their potential to compromise software availability. They are also no longer required to trust third party services that provide distributed file-sharing platforms, or implement their own complicated services.

Additionally, the system offers two-fold verification of the legitimacy of a given update.

- All pushed updates are digitally signed by the manufacturer, and copies of the public key are available on approved nodes. The nodes are then able to verify the validity of the update before accepting it.

- In order for an update transaction to be accepted into the blockchain, it must have originated from the manufacturer’s node on the blockchain. It is then mined by a given miner, and the transaction is placed on the blockchain to be quickly verfied by several other nodes.

By virtue of using a permissioned blockchain, untrusted devices cannot add themselves to the network. This limits attackers to compromising existing nodes in the network, which is more difficult.

Security Analysis

The three properties required for a secure system are confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Currently, our implementation of this system does not protect the confidentialilty of the firmware, but there are several methods for incorporating it as described in the future work section below. Integrity of the firmware is guaranteed by the immutability of the blockchain. We trust that the manufacturer pushes an innocuous version of its own firmware; the blockchain guarantees that any device will be able to access this firmware in its original form. Nodes can also independently verify the integrity of a firmware update by checking the manufacturer signature provided with each update. The availability of firmware updates is ensured by the private blockchain, which limits participant nodes to those whitelisted by the manufacturer. In the event that an attacker is able to compromise some participant nodes, a denial-of-service attack is still possible. However, an attacker would have to seize 51% of the nodes in the network in order to block the processing of new transactions. Without 51%, attacks can slow the network, but the efficacy of such an attack decreases as the size of the network scales.

A compromised participant node would also be able to attack its own smart home cluster. The damage that can be caused by this is limited to only the sensors and actuators for which it is responsible. A compromised miner may refuse to mine; we alleviate this problem by introducing more than one miner node in each cluster. Alternatively, the miner may choose to mine invalid transactions from another compromised node, thereby causing a fork. This is ineffective unless an adversary controls the majority of miners in the network.

If an end-device is compromised, it cannot cause any damage to the overall network. It is limited to damaging itself and devices it interacts with since end devices are not connected to the blockchain (they are not nodes). Furthermore, a compromised end-device will be visible to the miner node. The miner node is capable of warning users/the manufacturer, for example, when a device fails to update several times, or if a device is no longer communicating with the miner node [8].

Future Work

The most important item for future work is confidentiality of device firmware. Currently, we are forced to push the unencrypted firmware onto the blockchain. Pushing encrypted versions of the firmware would require encrypting the firmware with the public keys of every device in the network. We implement this as a proof of concept. As the system scales, this solution becomes untenable. A separate solution would be to push only a firmware update version identifier onto the blockchain. When it becomes apparent to a node that a firmware update is required, the node receives a hash or metadata file from the smart contract and attempts to obtain a copy of the update through peer-to-peer exchange with other nodes [8], [10], [11]. The manufacturer node also takes part in the peer-to-peer exchange for the first requests for the update, but after the update has propagated to enough nodes this will no longer be necessary [5]. A good candidate for this file exchange is the InterPlanetary File System protocol [7].

Currently, devices communicate via unsecured HTTP requests. A second necessary step to improve the confidentiality of the system is to establish shared keys between miner nodes and their corresponding devices. This will provide a way to secure all interactions in the smart home.

Web3 allows development of user web interfaces to interact with smart contracts in the blockchain. We have included a draft of a web interface that can be used by the manufacturer to control the smart contract. This allows for a simplified and intuitive interface on the user end. We have built a preliminary web smart contract interface for a different smart contract that stores sensor readings. In future work, this web contract interface could be tailored to allow vendors to upload firmware updates.

Though we have not implemented it in this project, this setup for firmware updates can be extended to implement permissions systems [3],[4]. The manufacturer can publish policies on the smart contract [5]. Sensors that want to write data to local storage on the miner make a request to the miner, and the miner subsequently checks the sensors permissions through the smart contract [6]. Permissions can be extended past data transfer to any functionality to which the sensors/actuators might request access.

In the case that the private blockchain is expanded to incorporate multiple manufacturers, we will explore the implementation of innocuous checking nodes to guarantee the validity of a firmware binary pushed from a manufacturer [8]. By virtue of consensus, a given device can be ensured that, although some nodes in the blockchain may be untrusted, firmware updates can still be verified as safe by the consensus of the network as a whole.

Conclusion

To conclude, we were able to provide an alternative means for remote, secure, and reliable firmware updates. We implemented a functional private blockchain with a single manufacturer node and 2 miner nodes, each responsible for a subset of Raspberry Pi embedded devices. Our method allows manufacturers to direct expensive server costs elsewhere while simultaneously keeping their firmware off the “public internet” and out of third party software repositories, while not compromising the speed at which updates become available after release. Overall, there is still room to expand this platform, such as expanding to multiple manufacturers, moving to a proof of authority model, or the implementation of a subscription-based payment model leveraging the currency oriented environment of Ethereum. The smart contract model gives the manufacturer flexibility in the rules they implement for their system. Further work must still be done to set this platform apart from other software update mechanisms that are largely in use today.

References

- N. Kshreti, “Can Blockchain Strengthen the Internet of Things?,” IT Professional, Vol. 19, No. 4, August 2017

- S. Huh, S. Cho, and S. Kim, “Managing IoT Devices using Blockchain Platform”, 2017 19th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), February 2017

- A. Dorri, S. Kanhere, R. Jurdak, and P. Gauravaram, “Blockchain for IoT Security and Privacy: The Case Study of a Smart Home,” 2017 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), March 2017

- A. Dorri, S. Kanhere, and R. Jurdak, “Towards an Optimized BlockChain for IoT,” Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation, April 2017

- K. Christidis and M. Devetsikiotis, “Blockchains and Smart Contracts for the Internet of Things,” IEEE Access, Vol. 4, May 2016

- Y. Aung and T. Tantidham, “Review of Ethereum: Smart Home Case Study,” 2017 2nd International Conference on Information Technology (INCIT), November 2017

- J. Benet. IPFS - Content Addressed, Versioned, P2P File System (DRAFT3), accessed on Mar. 17, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ipfs/papers/blob/master/ipfs-cap2pfs/ipfs-p2p-file-system.pdf

- A. Boudguiga, N. Bouzerna, L. Granboulan, A. Olivereau, F. Quesnel, A. Roger, and R. Sirdey, “Towards Better Availability and Accountability for IoT Updates by Means of a Blockchain,” 2017 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), April 2017

- K. Özyılmaz and A. Yurdakul, “Work-in-Progress: Integrating Low-Power IoT devices to a Blockchain-Based Infrastructure,” 2017 International Conference on Embedded Software (EMSOFT), October 2017

- B. Lee and J. Lee, “Blockchain-based secure firmware update for embedded devices in an Internet of Things environment,” The Journal of Supercomputing, Vol. 73, No. 3, March 2017, pp. 1152-1167

- B. Lee, S. Malik, S. Wi, and J. Lee, “Firmware Verification of Embedded Devices Based on a Blockchain,” International Conference on Heterogeneous Networking for Quality, Reliability, Security and Robustness, 2016, pp. 52-61

- N. Kshetri. (2018). Using Blockchain to Secure the “Internet of Things”. [Online]. Available: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/using-blockchain-to-secure-the-internet-of-things/

- J. Rowley. (2017). How Ethereum became the platform of choice for ICO’d digital assets. [Online]. Available: https://techcrunch.com/2017/06/08/how-ethereum-became-the-platform-of-choice-for-icod-digital-assets/

- G. Wood. Ethereum: A Secure Decentralised Generalised Transaction Ledger accessed on Mar. 20, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://ethereum.github.io/yellowpaper/paper.pdf